I hope that the following remarks will help to tie up a few threads I have been drawing out thus far pertaining to V's inscrutable desire, the status of violence and excess and the transformation of Evey into a revolutionary agent. In my view, the best way to do this will be to focus on Evey's decision to take V's place following his death.

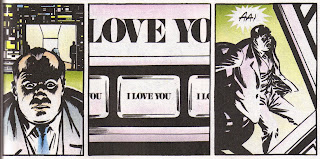

In the relevant scene, V collapses dead in front of Evey and she turns over in her mind what she will do next. The government has begun announcing that the 'terrorist' has been shot dead and that the insurrection is over. Without V to guide her, Evey is stuck with the weight of decision--what did V want from her? 'Oh Christ,' she laments, 'what happens next? You never said. You never said what you were educating me

for. You never told me what I'm supposed to

do' (249.2).

Considering her confusion about what V really wants from her, perhaps her impulse to remove his mask and see his 'true face' is a natural one. Yet, every time she removes his mask in her imagination, she only sees some other victim of the government that she has known: her mother (249.5), Gordon (249.8), her father (250.3) and finally herself (250.8). After this final revelation, Evey realizes who V must be. On the following page she looks at herself in the mirror and an extreme close-up shows her own mouth twisted into V's frozen smile (251.8). She later puts on his costume and appears before the masses to prove that the insurrection is far from over.

Here is perhaps the key moment in the entire text, the one to which all else has been leading. Evey, who has been looking to V as a sort of guarantor of her decisions, as the 'subject supposed to know' what she must do, finally assumes this responsibility for herself. In seeing all those she has lost behind his mask she fully embraces the necessity of revolutionary violence. Evey takes her final step towards becoming V, towards transforming a personal tragedy into a collective vendetta.

Her decision has negative resonances today in light of the 'war on terror' and thus

V for Vendetta proves particularly unsettling in its advocacy of violence, especially in the name of, as I am arguing, a sort of love. I have tried as much as I can not to project the contemporary situation into the text, but such comparisons are unavoidable and they are partially what account for its current importance.

Does Moore's text advocate terror? If so then can we take anything positive from it?

I think the unsettling nature of these questions speaks to the deadlocks of the current moment in which 'objective' (government sponsored) violence comes up against seemingly irrational 'subjective violence' (for more on this see my post on 'Law and Violence' below) in a self-perpetuating loop from which no one benefits. Yet, it also reflects an extremely narrow view of what 'violence' might mean in this case.

I recall here the distinction that Walter Benjamin makes between 'mythical violence' and 'divine violence'. He writes,

'If mythical violence is lawmaking, divine violence is law destroying; if the former sets boundaries, the latter boundlessly destroys them; if mythical violence brings at once guilt and retribution, divine power only expiates; if the former threatens, the latter strikes; if the former is bloody, the later is lethal without spilling blood... Mythical violence is bloody power over mere life for its own sake, divine violence pure power over all life for the sake of the living' ('Critique of Violence',

Reflections 297).

Benjamin's distinction between the mythical and divine sorts of violence maps well on to current concerns. Whereas one should openly condemn the bloody violence that keeps both terrorists and the governments they strike against trapped in a perpetual loop of 'mythical violence', entailing both 'guilt' and 'retribution', the later sort of 'divine violence' does not necessarily seek to engage in more such bloody violence. What of course constitutes a

divine violence is left unclear, but Benjamin quite directly indicates that he does not intend his definition to include terrorist violence exclusively--it is sometimes 'lethal without spilling blood' and always for the 'sake of the living'. Benjamin appears to advocate a strategic sort of violence that is more of a position against the law in all its functions than anything filled out with any positive content. To do so would necessarily fall into a mindless sort of resistance and ignore the particulars of the situation.

If read more as a parable for a particular position in relation to the law rather than a revolutionary program,

V for Vendetta actually opens up more options than it closes off. Nowhere does it say violence is the only modality of this position as an impossible object disrupting the smooth functioning of things. Rather, like the character of V, the novel as a whole refuses to tell anyone what must be done in their situation. That becomes a decision that each person must take in their particular place yet cannot be taken either with certainty or with guarantees. Ultimately, that seems to be the 'freedom' that V gives to Evey: the freedom over her own decision.

To do 'violence' to the law can mean a great number of things: protests, sit-ins, damage to property, strikes etc. Although containing numerous truths to reflect on for today, Moore's vision is admittedly exaggerated and the sort of violence necessary in that situation would differ greatly from in others. Nonetheless, perhaps Evey boils it down to the zero level. Her final act of violence is to look at the law which has destroyed her life and the lives of so many and to defiantly say 'no'.