In his use of extra-legal violence to exact his vendetta, V seems to operate 'outside the law'. Yet, making this claim would necessarily occur against the assumed background of an otherwise peaceful

socio-juridical order, which the novel makes abundantly clear does not accurately describe the regime in this near-future Britain, where violence, control, torture and intimidation are routine parts of daily life.

How then are we to perceive V's connection to the law?

Slavoj Zizek's distinction between 'subjective' and 'objective' violence could prove instructive in refining this question. According to

Zizek, 'subjective violence' describes seemingly irrational outbursts perceived 'against the background of a non-violent zero-level' or, in other words, the 'normal' and 'peaceful' functioning of things (Violence 2). In contrast, 'objective violence' describes the violence which sustains 'the very zero-level standard against which we perceive something as subjectively violent' (2). I think it is precisely this split between viewing V's actions as 'subjectively' violent (irrational

outbursts against society without cause) and seeing his violence as a response to an 'objective' violence (the disavowed violence that sustains the totalitarian state) that

constitutes the ideological parallax for the readers of

V for Vendetta: Will they see V as a terrorist who lashes out irrationally against a peaceful order, or will they perceive the repressed background of violence that compels V to act?

V for Vendetta certainly does not approach this question from a 'neutral' standpoint: it clearly favors the later

interpretation over the former. Before I develop this further however, I think it is important to note the 'political unconscious' of the text. Moore does not so much 'invent' some

exotic near-future out of nothing as extrapolate his

scenario from the conditions of 1980s

Britain. During this period, running parallel to the American 'Reagan Revolution', Margaret Thatcher and her Conservative party gained power in England. Along with this political shift came the ideological tenets of

neo-liberal ideology, which

essentially claimed that 'free-market' economics lead to the prosperity, freedom and 'personal responsibility' of citizens. Yet Moore seems to draw out the repressed underside of this revolution, pointing to its implicit xenophobia as well as its disavowed militaristic bent (in the U.S. one might point to the arms race, the history of imperialism,

racism of the 'war on terror' etc.). This historical shift forms the 'unconscious' of Moore's text and thus the critique of the novel should always keep in mind the historical situation as its 'absent cause' .

Returning then to the issue of law, one can see from

V for Vendetta how it relies on an irrational excess that it must actively disavow in order to function. Walter Benjamin makes precisely this point in his 'Critique of Violence', in which he argues that violence is an inherent component of the law, both in terms of its 'law founding' and 'law preserving' functions. From this perspective, law is itself based in irrational excess in so far as it must transgress its own boundaries in order to maintain its

monopoly on the

legit mate use of violence against those individuals who might threaten it. The main point here is that violence is not that which functions outside of the law, but instead is an irrationality that although

splitting law from within also sustains it.

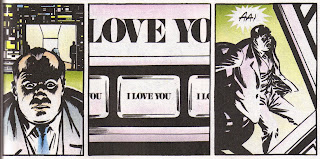

For now I will only develop one example to support this observation. In the sequence titled 'Versions' (37-41) the

fascist leader of the state (Adam Susan) rejects the notions of freedom and liberty, calling them luxuries that his country can no longer afford. Instead, he believes in the 'unity' brought about by the imposition of fascism. His language shifts into an

eroticized description of his

relationship to 'fate', whom he claims to love unconditionally, even if that love in completely

unrequited (38-39.3). Susan's obsession with 'fate' demonstrates how

fascism positions itself against the conditions of anarchy and any

disunified conception of society. In place of these conditions it establishes the inevitability (or 'fate') of an authoritarian leader rising to power who will re-establish order and posits the necessity of sacrificing freedom to this imperative.

In contrast, the other 'version' comes from V, who in the following sequence also uses eroticized language to describe his relationship to 'justice', represented as a statue. Whereas he admits that he had once worshipped what the statue represents, V quickly accuses her of turning into a whore for men in 'jack boots' and 'arm bands'. He then blows the statue up. So rejecting justice, he claims that 'anarchy' is his new mistress (41.2).

The juxtaposition of these 'versions' of law brings to the surface the differing function of violence in the state and in V.

The state must disavow the violence that sustains its power and instead ground its authority in something outside of the law such as 'fate'. The use of this term cannot help but strike the reader as remarkably similar to the

neo-liberal 'end of history' utopia in which it is only a matter of time before all countries submit to free-market and liberal democratic reforms. (Margaret Thatcher summarized it well with her infamous 'there is no alternative' statement.) Sliding under this

utopian unity is a systematic 'objective' violence necessary to sustain it: the

coercion that imposes reforms, extracts resources, exploits cheap labor, marginalizes minorities and

transfers wealth to those in power. It is this 'unconscious' level that we often fail to perceive in

neo-liberalism and

Vendetta brings to the surface.

Against this vision we have V who refuses to ground his actions in the notion of 'law', here represented as its ideological supplement, 'justice'. Instead he takes responsibility for his acts of violence with no goal of founding a new law. He does not actively disavow violence. Instead he mobilizes it against ideas such as 'justice' which have been used to conceal a deeper more systematic violence.

From the

perspective of the

neo-liberal state, V's violence appears as purely 'subjective': he is some kind of mad-man who acts purely out of his own disturbed psychological state. However,

Vendetta enacts a shift in perspective which forces the reader to perceive his violence against the background of a systemic 'objective' violence that produced him (he had been tortured in a concentration camp). It is precisely in this shift that I think we should locate the novel's political comment on the historical background of law in general and

neo-liberalism in particular. Although the state sustains itself by framing V's violence as an 'irrational' excess that only it can eliminate, will that same state confront the violence at its own core?

.jpg)